In my last article I explained the reasons why you should try Kotlin Multiplatform — not because it can do everything, but precisely because it can’t. It doesn’t do UI, or even attempt to. It does, however, do one thing really well: code business logic for iOS or Android. You code once, and deploy to either platform with virtually no hiccups because you keep the UI separate and native to its respective platform.

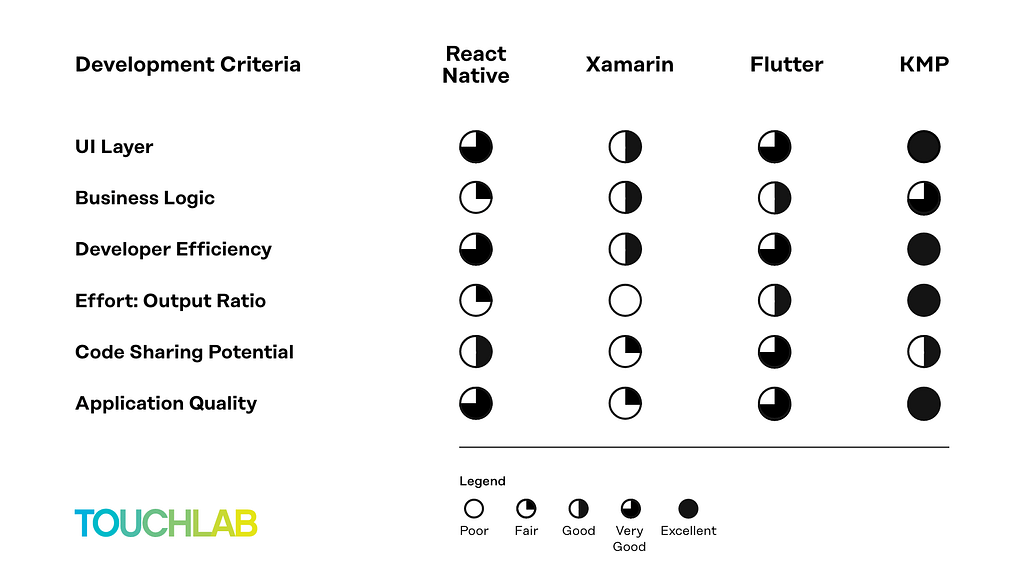

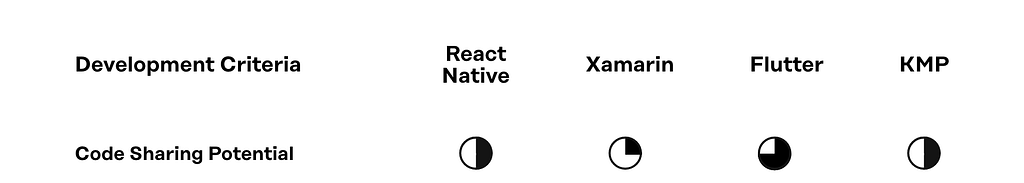

Naturally, introducing a relatively new way of coding immediately draws comparisons to other popular multiplatform solutions. The scorecard with which I concluded the article is meant to be a quick, point-by-point comparative glimpse at the three predominant solutions alongside KMP. Here, I wanted to provide some specifics on why we scored each the way we did.

UI Layer#

KMP#

Why rate KMP so high on UI when it doesn’t even have a UI layer? Because it doesn’t get in the way of the UI at all. Flutter, RN, and Xamarin all say sharing UI is a benefit to buying into their respective ecosystems — but each have gaps between expectations and reality. When using KMP, you code UI separately, in native, giving you greater control of the outcome for the best user experience possible.

Flutter#

Flutter doesn’t enable you to easily use native components to code UI. Instead, it takes control of all rendering, providing either a transparent view that shows the native Android code underneath, or uses PlatformViews which requires fairly clumsy native interop. Either way, it essentially co-opts the entire UI on its own canvas. And if there are bugs, you have to wait for the updates from Flutter.

React Native#

While you can create custom native UI widgets with React Native, Javascript performance is still an issue. Often, for example, developers will say it promises 60fps, but it gets in the way of doing good UI. It also hinders development efficiency because its UI widget libraries are not maintained by React Native.

Xamarin#

If you have a soft spot for .NET, Xamarin will be usable to you. But Xamarin.Forms has a lot of limitations, and Xamarin itself does not really create that ecosystem of great UIs. You’ll have to make separate UIs in Xamarin, Android as well as Xamarin.iOS, which is a lot more hassle than doing them natively. Similarly, this is why we don’t recommend writing UIKit code in Kotlin Native (even though you can).

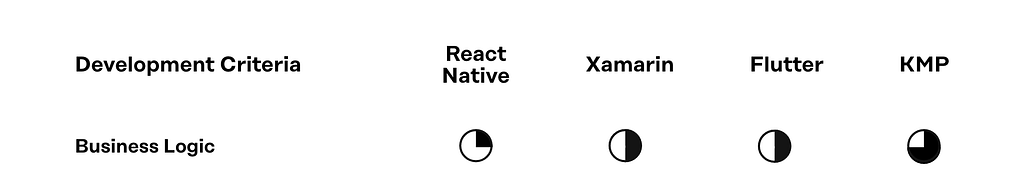

Business Logic#

KMP#

For Android, KMP is already as native as it can be. For iOS, it still has some issues with sharing business logic with idiomatic Swift code, but overall, it’s super-fast — and the native interop means you don’t have a bridge or channels to deal with.

Flutter#

At present, Flutter does not share business logic with native code adequately. The Flutter team is working at integrating it into native apps, but at this point it is still very experimental. When you need to integrate native code, you need to communicate across channels, otherwise you have to code it all in Dart — a language that is not widely used or supported. And while the Dart VM is fairly fast, it’s not as fast as a fully native solution. Basically, if you don’t want to deal with interoperability issues, it’s easier to work entirely within Flutter.

React Native#

To interop with native, it has to go through the JavaScript interpreter [update: Facebook knows this is a problem and recently released their own JS engine specifically for RN apps]:, so it’s always going to lag behind more native solutions. Also, it’s costly using JavaScript to bridge to native — more costly than Xamarin or Flutter.

Xamarin#

Essentially, Xamarin presents the same problem as Flutter does: no direct interoperability with native code. You have to use C++, JNI, Java, Kotlin, or Objective-C Bindings. Currently not possible to interop with Swift, you can’t share business logic with non-Xamarin apps at all, and Microsoft has no plans to do this.

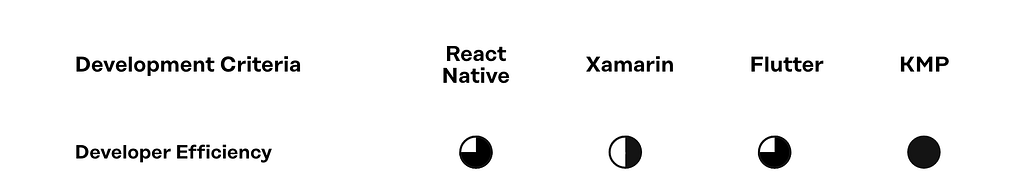

Developer Efficiency#

KMP#

Debugging is straightforward with KMP because the debugging tools you’re already using are compatible. Android coders can debug in the Kotlin IDE, and iOS coders can debug in Xcode. In the meantime, as the libraries for KMP continue to grow, you’re not locked in — just use the tool that makes sense for that ecosystem.

Flutter#

With Flutter, you need a wrapper for its libraries to communicate with native code.You can’t use Xcode for iOS development. And while you can use Android Studio, you’re not really building an Android app with Flutter, you are building a Flutter app and using the Flutter plugins. Essentially, you’re in foreign territory.

React Native#

Facebook has put a lot of effort into React Native, enabling you to choose from many great debugging tools and IDEs with good integration. It has a large and growing community that stems from the web development ecosystem. Even so, you’re unable to use the native libraries as easily as you can with KMP, so you still need to put work into libraries that haven’t yet been ported and integration with existing apps. And if you aren’t already a web shop, you need to learn the whole ecosystem.

Xamarin#

To integrate existing native libraries, only supports binding to ObjC Frameworks, and requires Java Bindings or the JNI. Sometimes, you can’t bring any new frameworks from native iOS or Android into Xamarin Projects. Additionally, you need to use LLDB or GDB for debugging native code.

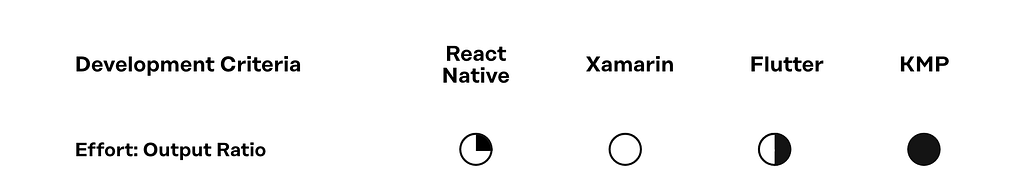

Making the most of multiplatform#

KMP#

With KMP, Android is already fully native, so a bridge is not necessary. And, on iOS, KMP compiles a native framework with Objective-C headers, so, again, a bridge is not necessary. You can easily take a mostly business logic Android library and make it work as a KMP library (even easier if it’s already written in Kotlin). And while the UI has to be separate, it’s not a problem because the UI can then be a very thin layer that’s not dependent on the business logic layer.

— Common architecture practices like MVP, MVVM, and CLEAN already encourage separating business logic and thinner UIs. It’s only a slight modification to accommodate the shared module layer.

Flutter#

Taking an existing Android library and making it a Flutter library is a whole lot harder than it is when using KMP. Flutter is really designed to be its own self-contained ecosystem. It’s difficult to share with non-Flutter apps. And while sharing the UI is better than it is in React Native or Xamarin, you have to build your own libraries, or write in Dart.

React Native#

React Native is not ideal for larger apps or larger teams, and even though the developer community is large, it’s mostly made up of web developers, and therefore not necessarily attuned to mobile development fully. There are significant differences — screen sizes, UI expectations, variable device performance due to CPU, RAM, and graphics chips variability, offline and low or unreliable network connectivity, and platform-specific innovations that have been driven by significant engineering investment from Apple, Google, and Samsung.

Xamarin#

Xamarin has its own ecosystem, with a relatively small developer community, and very limited sharing with other ecosystems. You have to build the UIs in Xamarin.Forms, or you have to build them separately using C# in Xamarin.Android and Xamarin.iOS.

Potential for code sharing#

KMP#

Even though KMP does not share the UI, which limits how much you can share, you are able to architect the app so that the UI layer is as thin as possible, which in fact is good architecture practice anyway. And it’s also good practice to make the best UI for users, which requires UI divergence between platforms anyway. Using KMP, you won’t run into obstacles when the UIs do need to diverge. And you will more easily be able to share non-UI code with less of a performance cost.

Flutter#

Flutter provides everything except platform-specific features, which require a channel to native code. So if a library you need already exists in the Flutter ecosystem, great. But if not, you need to create it yourself which essentially requires writing code for three platforms — Android, iOS, and the Flutter Package API to communicate with the platform-specific implementations.

React Native#

React Native provides everything but platform-specific features or high-performance logic (making it less desirable than Flutter), each of which requires a bridge to native code. If a library you need already exists in its ecosystem, you’re set. If not, like Flutter, you need to create it yourself, which requires writing code for three platforms — Android, iOS, and the React Native Bridge Module.

Xamarin#

For simple apps, Xamarin.Forms allows you to share close to 100%. But it’s not ideal for more complex apps, where a lot of UI and any platform-specific features need to be separated into Xamarin.iOS and Xamarin.Android projects.

Maximum App Quality#

KMP#

When coding with KMP, you get fully native UI and business logic, with the same app quality as fully native apps in iOS or Android.

Flutter#

While the UI is performant (“buttery smooth” as the Flutter dev-rel people like to say), it’s easy to end up with something that’s perceived as lower quality to seasoned users. Also, Dart VM is fairly fast — much faster than Javascript — but there are still channel overhead issues you must deal with. As well, support for older devices is not robust. For Flutter in particular, the UIs may look modern on older devices, but the performance may be worse than native UI and implementation.

React Native#

On the positive side, React Native architecture encourages native views and widgets, so you don’t fall behind platform UX updates. (Users expect these; otherwise, apps start to look old to them.) There is, however, a higher risk of lower performance because of Javascript (especially true on Android devices where standard Javascript is about as performance as an iPhone 6s and Facebook recently released their own engine specifically for RN apps on Android).

Xamarin#

For Xamarin, UI is really an afterthought. Xamarin.Forms has been getting more attention recently, but even when incorporating native widgets, you end up writing a full app in Xamarin.iOS and Xamarin.Android before getting something that modern users would generally accept as good quality.As for performance, it is true, the MonoVM is fairly fast, but there are still bridging overhead issues.

This post originally written for Touchlab